Jet2: Not just an airline

Jet2 trades at only 1.1x net cash and 7x earnings - despite being as much an asset-light travel company as an airline.

For any British readers, you’ll probably know Jet2 as the company with the in-your-face ads that have been milking the hell out of the same annoying Jess Glynne song for the past 9 years.

For anyone else, you probably haven’t heard of the company. That’s because these guys do one thing, and one thing only — ship British tourists to European holiday destinations. (Usually on package holidays to third-party hotels.)

Turns out this strategy works — between 2010 (when package holidays became what Jet2 do) and the months before covid, the stock returned ~40x — a 43% CAGR.

But since then, the stock’s performance has been mediocre:

That’s not to say business performance has been lacking — quite the opposite. Jet2 recovered faster than any other major UK airline in the wake of the pandemic, and has now doubled revenue (and 2.4X’d pre-tax profit) compared to 2019. The company entered the pandemic with a 14% market share - and exited it with 21%. It now leads the UK package holiday market, just ahead of Tui. And yet, the stock has gone nowhere since early 2020.

This has left Jet2 trading at just 7x earnings, despite holding net cash now equal to ~90% of the market cap. So what the hell is going on?

Business Overview

The most important thing to understand with Jet2, in my view, is whether it’s an airline. (Chris Waller from Hidden Gems Investing would argue not.)

I mean, they definitely have an airline. But 70% of their customers are on package holidays, and these guys pay about 3.5x as much for a package holiday (£905 on average) as they would for 2 flights (£260) — which implies almost two thirds of Jet2’s total revenue is attributable to all the other stuff (hotel, transfers, excursions etc.).

Then again, if they’re just selling all of this on without really collecting any extra profit on it, then economically they’re essentially just an airline.

I think there are two decent ways to get to the bottom of this, though neither of them will be perfect.

The first is to work out what we’d expect revenues to be if they only sold flights, and compare the “margin” on that number to the industry’s average profit margin. For the first half of that, we can multiply 17.7 million passengers in FY24 by £114 average flight-only ticket plus £26 average non-ticket revenue per flight to get £2.5 billion expected flight-only revenue. Operating profit was £428m, for an effective margin of 17.2%. IATA reckon the European industry’s overall margin was 6.8%; though the unweighted average was 8.5%. If the airline bit of Jet2 was an average airline, that would imply Jet2 is getting 50-60% of its profits from non-airline stuff.

The second way is to compare return on airline-related assets (which I’ll take as being gross PPE). Here, we find Jet2’s 14% is about double the industry average of 7% (by my calculation).

So Jet2 is about 50% airline.

Of course, that assumes the airline within Jet2 performs only averagely, which I think is probably not the case, given how well-run the business as a whole is. But I don’t think that really matters — if they’re actually 65% airline by profit, but the airline is 30% more profitable than the average airline, that’s fine. What matters is that the things that make airlines suck as investments — the low returns on capital, the cyclicality, the exposure to oil prices — all apply less to Jet2. If oil prices spike and everyone else’s profits drop 50%, Jet2’s should only drop ~25%. That’s obviously an engineering approximation (π = e = 3) but you get the point. Anyway…

Why do Jet2 win?

Jet2 were far from the first package holiday operator — in fact for most of their history they were David, up against the Goliaths of Tui and Thomas Cook. What was it that allowed them to add ~2% market share per year, every year for the past decade?

I think the most important factor is their incessant focus on the customer experience. This sounds wishy-washy, but there is plenty of evidence that they really stand out here:

Jet2.com, the airline, placed 19th in the most recent UK Customer Satisfaction Index. No other airline was in the top 50.

The package holidays business, Jet2Holidays, placed 14th, the highest in the tourism category.

Jet2 won the Which? Travel Brand of the Year award for 2024

60% of package holiday customers book another Jet2 holiday within 2 years. The same figure is just 40% at Tui. Jet2’s number would be even higher if it wasn’t growing so damn quick, too.

They don’t bloody shut up about customer experience in the annual report

Of course, Thomas Cook’s collapse didn’t hurt, either.

One last note — a lot of Brits see Jet2Holidays as a "cheap and cheerful” brand, but this isn’t really the case. The average price of a Jet2 holiday is £900 (similar to Tui on a per-night basis, at least for short-haul), and more than half of package holidays are to 4 or 5-star hotels.

Management

When former pilot Philip Meeson bought Channel Express Group in 1983, it was a sleepy cargo micro-airline, operating a handful of Handley Page turboprops out of Bournemouth airport.

Over the next 20 years, with Meeson at the helm, it would steadily scale up operations — adding first some Fokkers, then some Boeings, and then in the late 90s, beginning to offer passenger charter flights. Then in 2002, with Ryanair and EasyJet reporting record results as legacy carriers floundered in the wake of 9/11, Meeson finally decided it was time for the group to launch its own low-cost passenger airline. Jet2 was born.

You already know most of the rest of the story — rapid growth, expansion into package holidays, and further rapid growth, to finally surpass Tui in 2023 as the UK’s largest tour operator. And through the entirety of these 40 years, one thing remained constant — Philip Meeson at the helm.

But in Sep 2023, at 75, he decided it was finally time to throw in the towel.

In fairness, it wasn’t a sudden move. Over the preceding few years, he’d been quietly devolving more and more responsibility to his CEO, Steve Heapy (who took up the role in 2013). By the time he retired, his role was much more akin to the traditional “Chairman” than the active role the ‘Executive Chairman’ title implies.

So, it’s Heapy we should be spending most of our time on. What of him?

I think he’s pretty good. I mean, he should be — Meeson had a very long time to find and nurture the right person. And the business hasn’t performed any worse over the last few years than it did prior, operationally.

But also, I think he says the right things. For example:

How do you look back on the refund saga early in the pandemic?

”When you look at the actions of some of our competitors who either delayed or refused to pay back money — put another way, they stole money — well, I’m quite happy to put the boot into those rivals, because they acted very irresponsibly. They treated their customers with disdain and tarnished the reputation of the holiday industry. Some of these companies should hang their heads in shame. The industry now has a reputation similar to that of estate agents and bankers, and that’s not right.”

Did things ever get desperate for Jet2 in the peak of the pandemic?

”No, we took very early action. We did two share issues and a convertible bond, going to the markets to raise cash early. You have to raise cash from a position of strength and not wait until the last minute.”

Any plans to take the company long-haul?

”Not at the moment. We’re already the biggest tour operator to the Med, and I think there’s a lot more we can do there. It’s always very dangerous for a company to get carried away and want to start taking over the world. But never say never.”

Capital allocation record is another key point to consider. There have been two major decisions on this front in the last few years.

One of those was raising capital during the pandemic. They did two share issuances — one for 30 million shares at £5.76 in May 2020, another for 35 million shares at £11.80 in Feb 2021 (shares are now ~£15). Together these expanded the share count from 150m to 215m, by 43%, while raising just under £600m.

In hindsight, that looks like a pretty poor move, especially the first one. The company went into the pandemic with net cash of just over £1b, and FCF in FY21 (Apr ’20-Mar ’21) was only £870m. Obviously, that’s not the kind of margin you would want to scrape by on, but they could have raised debt. Then again, May 2020 was a very uncertain time — banks wanted nothing to do airlines, so Jet2 would probably have had to gamble on their cash reserves lasting until banks are finally ready to lend to them. That’s a big bet to make when something that literally hasn’t happened before happens (the lockdowns, not the pandemic itself). I think it would be unfair to judge them too harshly on this.

They also issued £390m of convertible bonds in June 2021. These have a reference price of £12.90, conversion price of £18.06, bear interest at 1.625%, and mature in June 2026. This seems like a pretty good move, to me. In the worst case scenario, shares hit the conversion price, but they could theoretically buy back 22 million of the 30 million they issued, just with the proceeds — so the sort of “economic” dilution risk in issuing these was only ~8 million shares, or about a 4% increase in share count. And hey, from my perspective, if shares hit £18.06 before June ‘26, that’s at worst a 15% IRR for me.

The other major capital allocation decision was their order of 146 Airbus A321neo aircraft. For reference, their fleet beforehand was about 110 planes, so this was a BIG order. I’ll talk more about it in a second — but first we need to look at the current financials.

Financials

Not sure any commentary on those numbers is needed. Just solid, consistent long-term performance. Nor does it seem to me that any adjustments are necessary to get a normalised number.

Currently, at a share price of £15.47, the market cap is £3.32 billion. That’s only 6.7x TTM net income of £496m.

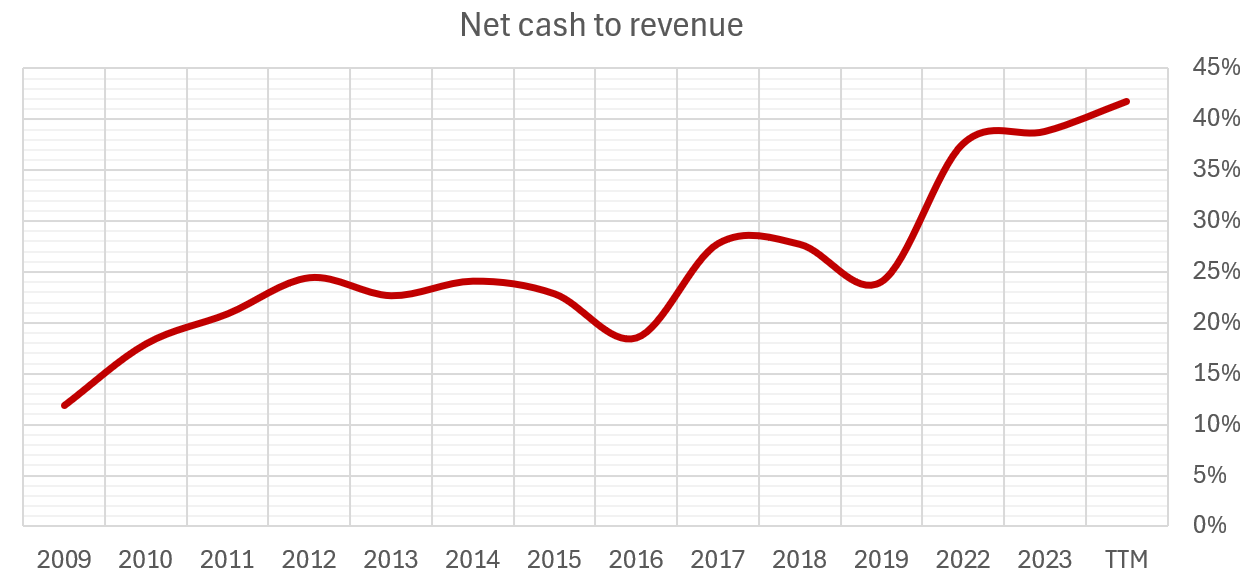

Plus, the cash balance has exploded in recent years:

42% of revenue in net cash is a pretty unusual number for an airline (as mentioned earlier, it also happens to be about 90% of the market cap). Most run gross cash as 20-25% of revenue. Even if we subtract all of Jet2’s lease liabilities, we’re still looking at 33% of revenue/70% of mcap in net cash.

If we assume they only need 25% of revenue as net cash (which would still be very conservative), that frees up £1.2b — implying a valuation for the business itself of only £2.1 billion, or just over 4x earnings. That’s my kinda multiple.

However, this cash is not going to be returned to the shareholder anytime soon. That’s thanks to the aforementioned Airbus order, which it’s about time we talked about — as it will be the dominant force shaping Jet2’s next decade.

The Order Book

Between 2021 and 2024, Jet2 placed orders for 146 A321neo, with a delivery schedule starting in 2024 (they’ve taken 13 so far) and ending in 2035.

This is a massive order — the “total transaction value”, including inflation uplifts and customisation costs, is estimated to be ~£14.5 billion before discounts. That’s a scary number for a business with a market cap of only £3.25b.

Discounts matter, though. For whatever reason, it’s standard practice for Airbus and Boeing to offer discounts to list prices of >40% for large orders, and this one is no exception. Terms of such deals are always closely kept as commercial secrets, but you can get a pretty good inkling from the financial statements. In FY24, Jet2 recorded additions to aircraft & components of £305m. They took 6 deliveries during the year — which means the actual price paid per aircraft couldn’t have been more than £51m (and it may have been meaningfully less, if a significant chunk of that £305m was related to major maintenance on their existing fleet). £51m would equate to a discount of ~50% to the ~$125m list price of an A321-neo.

(If you think 50% off sounds like a lot, Gridpoint estimated that O’Leary may have gotten as much as 69% off on Ryanair’s massive Boeing MAX 8 order - that’s why he’s the GOAT-)

As confirmation, in the Sep 2024 interim results, Jet2 estimated the next 7 years will see gross capex of £5.7 billion. They didn’t say exactly how many of the 136 then-outstanding orders were for before Sep 2031, but I’d estimate it to be in the region of 110. Allowing for £700m of other capex, this would imply £45m per plane, which aligns nicely with the somewhere-below-£51m I came up with a second ago.

Anyway. The big questions here, to me, are:

How much will fleet size expand? These planes will partially be replacing the company’s 100 Boeing 737s, which are now 16 years old on average. If the Boeings are all sold, we’ll be looking at around a 30% expansion compared to the last summer’s ~110 owned planes. However, if demand is strong, they have the option to hold onto a good chunk of the Boeings, lease some additional planes, or even order a few more — so it’s not like they’ve limited themselves to 30% volume growth over the next decade.

Can they afford it? They certainly won’t want to spend down all their ~£3.6b in cash — management have made it clear they see any cash resulting from customers pre-paying for holidays as the customer’s cash. But they’ve still got about £1.2b of “own cash” (very seasonal) which they’ll happily dig into;

EBITDA (yes, that is the right tool for the job here) was ~£750m in FY24, so under a no-growth assumption we’d be looking at ~£5b of EBITDA in the next 7 years.

Finally, they can probably sell the Boeings on for ~£8m each, so that could generate another ~£600m over 7 years.

Altogether that would be about £7b, meaning they shouldn’t have any trouble shelling out that £5.7b over 7 years. If industry margins remain at similar levels to today (big if), they shouldn’t even need to take on any incremental debt.What’s the IRR? Estimating this requires a bucket-load of assumptions — aircraft price, payment schedule, utilisation, pricing, fuel cost advantage of these efficient new planes (and how quickly that gets competed away as everyone else gets them), — the list goes on. I’ve done a bunch of Exceling, using what I’d consider to be a reasonable range of assumptions, and can confidently tell you that the pre-tax IRR is probably maybe between 12% and 22%. My best guess is around the 17% mark, but the error bars are pretty wide. Post-tax, that’s about 13%. So not incredible, but meaningfully above the cost of capital.

Risks

This will be a far-from-comprehensive overview of a few of the key risks. If this post piques your interest in the stock, please don’t assume this is all that could go wrong.

First, the generic airline risks:

Overcapacity — overall airline industry margin is closely tied to the ratio of capacity (usually defined as seat-flights or seat-miles) to demand (passengers or revenue seat-miles) — naturally. A constant stream of ambitious new entrants and overzealous existing players adding more capacity than the demand justifies is a big part of why the airline industry is so famously awful for investors. 2013-2019 is generally considered to have been a period of “capacity restraint” in Europe, where this tendency receded, but that seems to be over now, looking at the massive aircraft orders some major players have been putting in. It’s not a death sentence — a lot of the order book is on option, rather than firm buy, and excess capacity can be leased or sold to other regions, but it does imply a good chance the overall industry margin will drop, in my view.

Oil prices — fuel makes up a good ~30% of an average airline’s expenses. After Emissions Trading System allowances are phased out in the next couple years, that will rise to nearer 40%. Fuel cost changes tend to get passed onto the consumer fairly quickly, but higher ticket prices reduce demand, which widens that demand-capacity gap — so if oil moves higher it’s still a negative. Plus, airlines sometimes have to eat some of the higher cost themselves, to avoid annoying their loyal customers too much.

Technical problems — issues with planes, for example the Pratt & Whitney engine issues seen over the last few years, can seriously damage the bottom line. Just look at Wizz Air’s 5-year chart.

A crash — this is an ever-present risk for airlines, and more so for low-cost operators, whose reputation is more fragile. While Jet2 probably aren’t as exposed as Ryanair or Wizz — which both regularly receive accusations of poor safety standards and generally have more junior pilots — I still wouldn’t be surprised to see the stock gap down 20% if the worst did happen.

Then there’s the Jet2-specific risks:

Management — I like Steve Heapy so far. He seems to be doing a good job. But I could be wrong — maybe he’s just being temporarily sustained by the strong existing culture there. He could also leave, though I think that’s unlikely considering he’d been preparing to take the reins for a full decade, as CEO under Meeson.

Poor ROIC on new fleet — taking the deliveries while remaining fairly debt-free will take virtually all of Jet2’s free cash. If the return on this investment is substantially lower than I believe, the stock’s performance from here could be mediocre.

A bunch of others — some of which I’m aware of and think aren’t significant enough to warrant individual discussion; many of which I am completely unaware of, because that’s the nature of investing.

Conclusion

I think Jet2 is an above-average business, lead by above-average management, trading at a below-average multiple. It doesn’t feel like a homerun or a mid-term 10-bagger to me, but it does feel like a solid medium-size position to slap in my portfolio.

Fantastic Post

This is a nice write-up, thank you. I've looked at Jet2 before, though not in this detail - if I were to invest in an airline operator, this is the one I would choose.

And, as an engineer, your engineering assumption definitely raised a chuckle! Nicely done!