Maybe it's not so efficient, after all...

A couple of recent examples of the market behaving, seemingly, quite inefficiently.

It was only a couple of weeks ago that I posted this note, arguing that you should always have the null hypothesis that it’s you missing something, not the market — and insist on very strong evidence before deciding otherwise.

But recently, there have been two occurrences — specifically, market reactions to earnings reports of stocks I own — that have just struck me as completely irrational. And before you think I’m just salty, in both cases the movement was actually in my favour. I just don’t think it should have been.

Case #1 — Airtel Africa

AAF was one of the first stocks I ever wrote about. When I published that piece, the company had just reported a ~£1 billion currency-related loss due to the Nigerian Naira’s enormous devaluation, which took FY24’s earnings into the red.

But this loss didn’t really reflect economic reality, if looking at the business from a USD perspective. It arose because local African subsidiaries held USD-denominated debt — these subsidiaries reported financials in local currency, so as the dollar appreciated, their local currency-translated liabilities expanded and they reported losses. When the subsidiaries’ financials are then consolidated onto the parent company’s, this loss is kept — even though the parent reports in USD (and moreover, high inflation following a devaluation counterbalances the initial decrease in USD-denominated cash flows, so terminal cash flows aren’t really affected).

At the time, I wondered if this loss was part of the reason I could buy this high-quality, high-growth business for <9x owner earnings (recent capex guidance makes me think the multiple was even lower in hindsight). I decided not — and instead put it down to the combination of being (1) a dirty telecom business, (2) in Africa, (3) with a fair bit of debt (through that lens, 9x is almost generous).

NCC Decision

The first little bit of potential inefficiency was the market’s reaction to the Nigerian Communications Commission finally caving and raising the price cap (read: price) of data, calls and texts by 40%. Given Nigeria accounts for something like a third of profit, that seemed to me like it should move the stock up meaningfully. The announcement was made on Sunday 26th December — yet the next day, the stock opened flat from Friday.

That struck me as weird, but I chalked it up to the decision being priced in — prices had to go up at some point, I guess, and maybe if they’d held off a little longer, some weaker competitors would have withdrawn from the market (as MTN was threatening to do).

Q3 Earnings

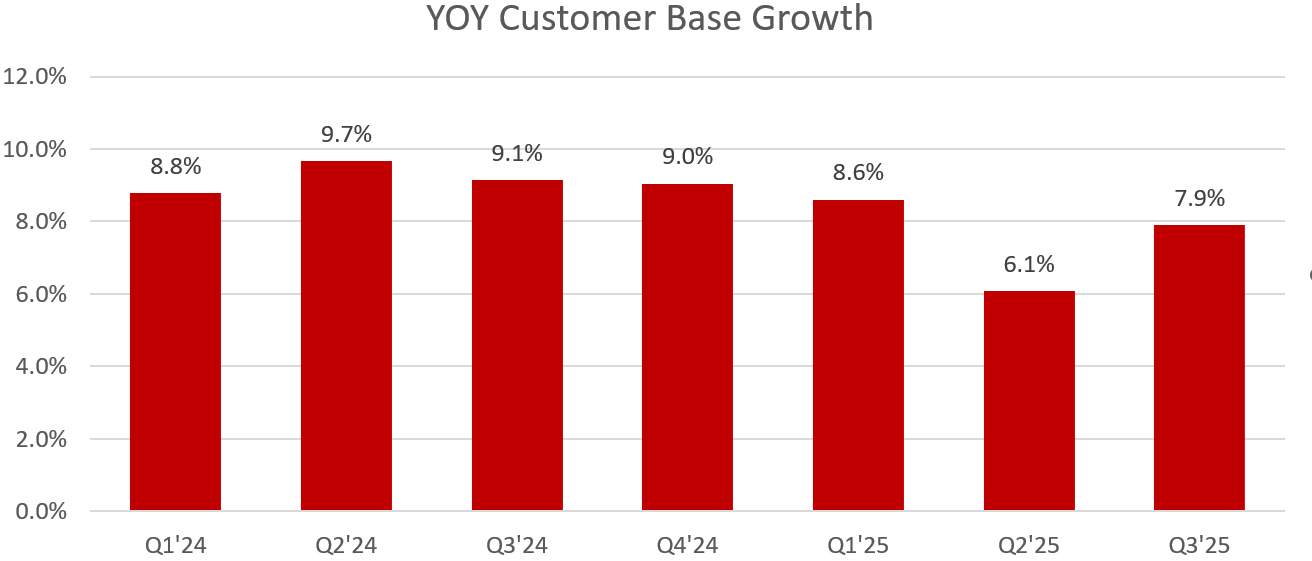

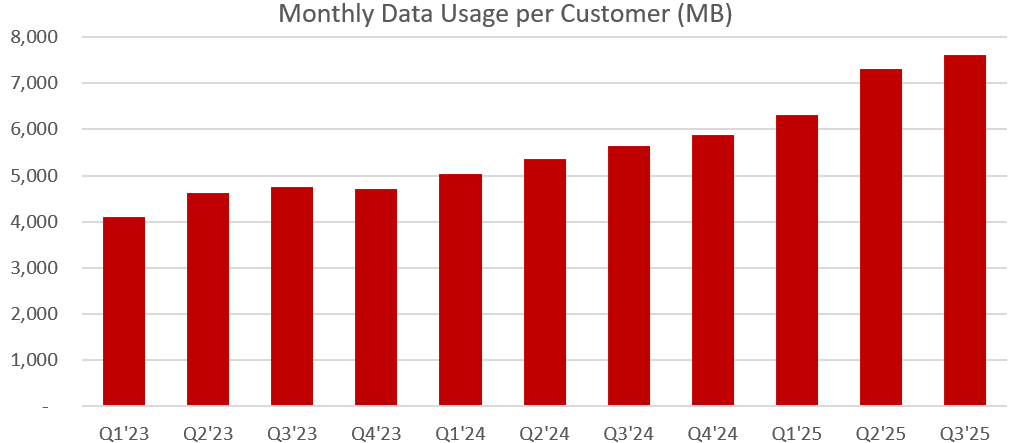

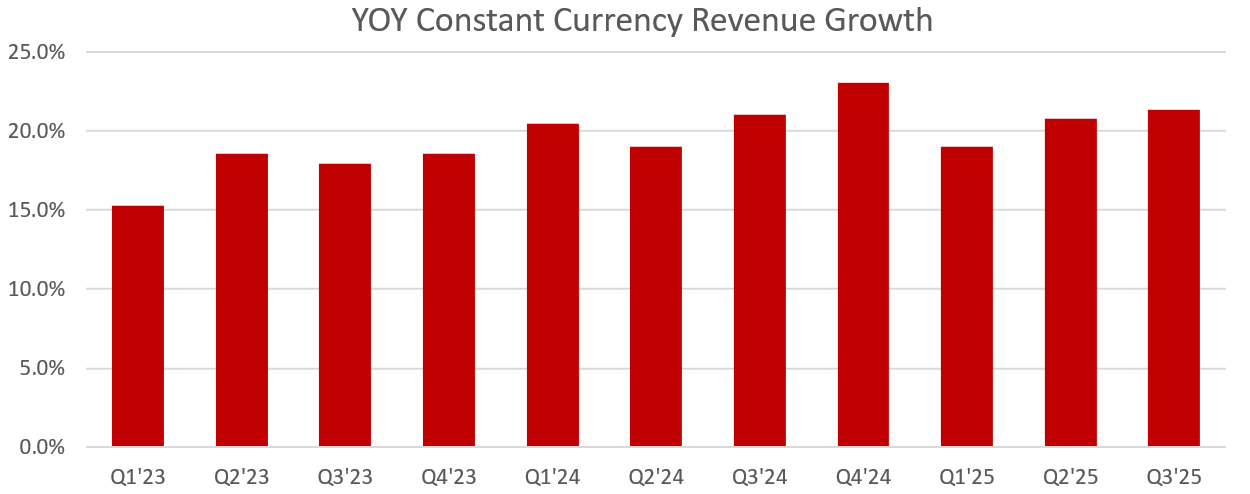

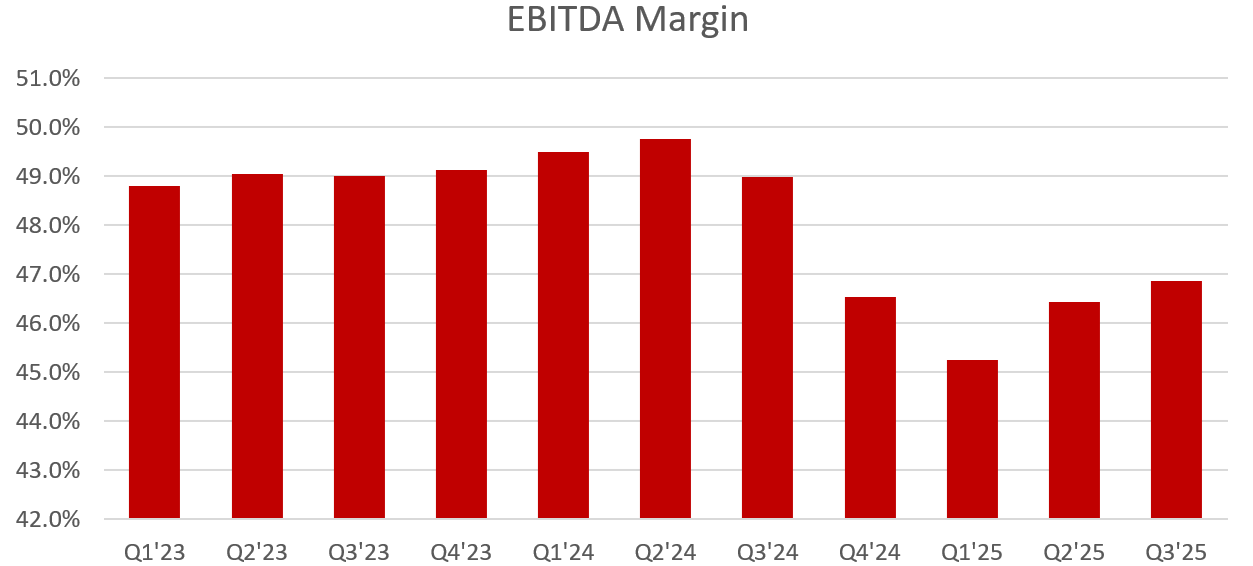

But then Q3 earnings came out. To my eye, they were normal in pretty much every way. Subscriber count, data usage per user, constant currency revenue growth, EBITDA margin — all in line with the recent average/trend:

Don’t get me wrong, a perfectly fine set of results. But nothing out of the ordinary. I was expecting the stock to be flat, or maybe up a couple percent. Instead, having already run up 38% in the last 2½ months, the stock popped another 10%. Cumulatively, the stock was now up 52% in less than a quarter, seemingly without reason.

Well, there was one thing that was different about Q3’s results. The currency losses that had been plaguing their financial statements had suddenly swung to a $144m gain, as some African currencies regained a bit of ground against the dollar.

It’s not just my reasoning around how these weren’t really losses that makes this irrational/inefficient. It’s also the fact that these currency losses/gains can be easily predicted, with reasonable accuracy, by looking at exchange rates. For example, Q3’s gain was primarily caused by the Naira and the Tanzanian Shilling. Here are their exchange rates:

I’ve not bothered to do the maths myself, but for the Goldman analyst slaving away 16h/day, I’m sure it wouldn’t have been that hard to work out this quarter was gonna see a gain. And yet, the stock is up enormously, and I can see no other reason why.

(Unless the market was just delayed pricing the NCC decision in? But that would still be inefficient — the market should react instantaneously to new information.)

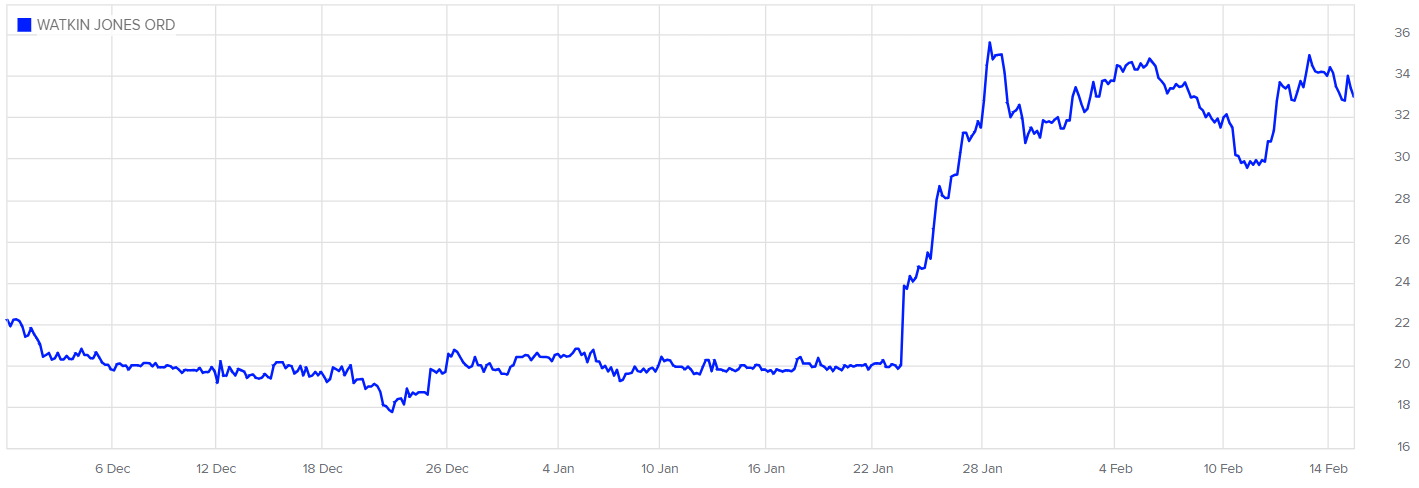

Case #2 — Watkin Jones

It was this one that prompted me to write this piece.

Watkin Jones (WJG.L) was a weird one from the start. When I first came across it a month or so ago, I found its valuation pretty baffling — it had a market cap of £50m, with forward net cash of £70m and TBV of £121m; and prior to 2023 they’d been earning £30-40m per year. Granted, recent results had been a lot worse — about breakeven before a £40m provision for building safety remediation (thanks to Grenfell) — though poor results have been an industry-wide thing recently.

However, the TTM results also included a £5.5m impairment of land assets and a £4.6m loss on disposal of an investment property. Crucially, these were not marked as exceptional items. Setting these aside, the TTM pre-tax profit was about £13m. A poor margin on ~£400m of revenue, but still a super low multiple on depressed earnings. I bought, in reasonable size.

Then the full-year results came out.

At first glance, they looked pretty good. Reported profit before exceptionals had swung from -£2m in FY23 to £9m in FY24. The market reacted accordingly — shares gapped up 20%, and over the next few days, that turned into +65% (To be honest, this annoyed me more than anything — partially because I hadn’t yet finished writing it up + adding to the VGV Portfolio; and partially because in hindsight, I had probably sized it too small for my conviction). It remains there today.

However, digging a bit deeper into the numbers, FY24 didn’t include the aforementioned impairment & disposal losses — so that was already a £10m YOY boost to “pre-exceptional” income — but it did include a £6.3m profit on divestment of a partially-completed project. Excluding all of these, earnings had actually fallen from ~£10m to ~£3m.

Granted, a sale of an existing project isn’t completely non-underlying — but that £6.3m probably would have been recognised over a couple of years otherwise.

So this stock rallied 65% on results that were both worse than previous ones, on a truly underlying basis, and worse than I expected.

What’s the Takeaway?

I still think the note I referenced at the start — about first presuming the market is right — is good advice. A quick anecdote, to make the point: just yesterday I saw a post complaining about how a US tech company had reduced the next year’s sales guidance 10% and the stock had jumped. I was immediately skeptical, so checked the report and, while they had reduced the guidance as described, the effect was only to bring management’s guidance into line with analyst’s expectations. In other words, the 10% reduction was priced in. Moreover, they simultaneously issued some incredibly aggressive guidance for the following year (65% YOY revenue growth, vs. analyst consensus of ~20%). The market had not behaved at all irrationally — a rally was the “correct” outcome.

But there is a commonality between the two market weirdnesses I’ve talked about here: in both cases, there was a good reason for the irrationality.

In Airtel Africa’s case, you have strange, complex accounting messing earnings about, on an African company which is 74%-owned by its Indian parent — so not the most followed company in the world. (To be honest, still not completely sold on this — it is a £4-5 billion company after all. If I’ve missed something let me know.)

In Watkin Jones’ case, you have a £50m market cap — so followed very little — and management electing not to mark unfavourable one-time charges as exceptional. I’d almost be a little surprised if the market got all the nuances right, when you get this small — that’s why I like fishing down there.

The other commonality is that these are both London-listed stocks. I do wonder if a part of this is that UK analysts are a little more traditional and a little more cautious about heavily editing the GAAP numbers.

As for how to use this? Well, if I was a gambling man, perhaps I’d have a go at trading AAF’s next earnings on the basis of the quarter’s forex moves. But alas, I am not. So I think the key takeaway is just yes, first presume the market is right, but if it really seems like the market might be wrong, and you have a good reason to believe it would be — back yourself.

If you appreciate the work I put out for free, the best way to help is like the post and share it with a friend. Thanks!

Until next time,

Matt

I've held AAF for a few years and found the move over the past couple of months confusing too. I wondered if most of the move is in anticipation of the mobile money IPO this year. Would say ~50% of the analysts had an IPO related question in the recent earnings call, despite management keeping pretty tight lipped about any of the details for now.

When I'm analysing a stock, I will always decide for myself what to consider as exceptional or operational - partly for consistency across multiple companies, and partly for the reasons you describe here. Normally, my assumptions align well with the annual report, but every so often you get dividends from investments in operational cash flow (but they are not from the business in question's operations), or sale of assets or businesses in the non-exceptional categories, which I personally don't like - I consider all such transactions as non-recurring and therefore exceptional by nature.